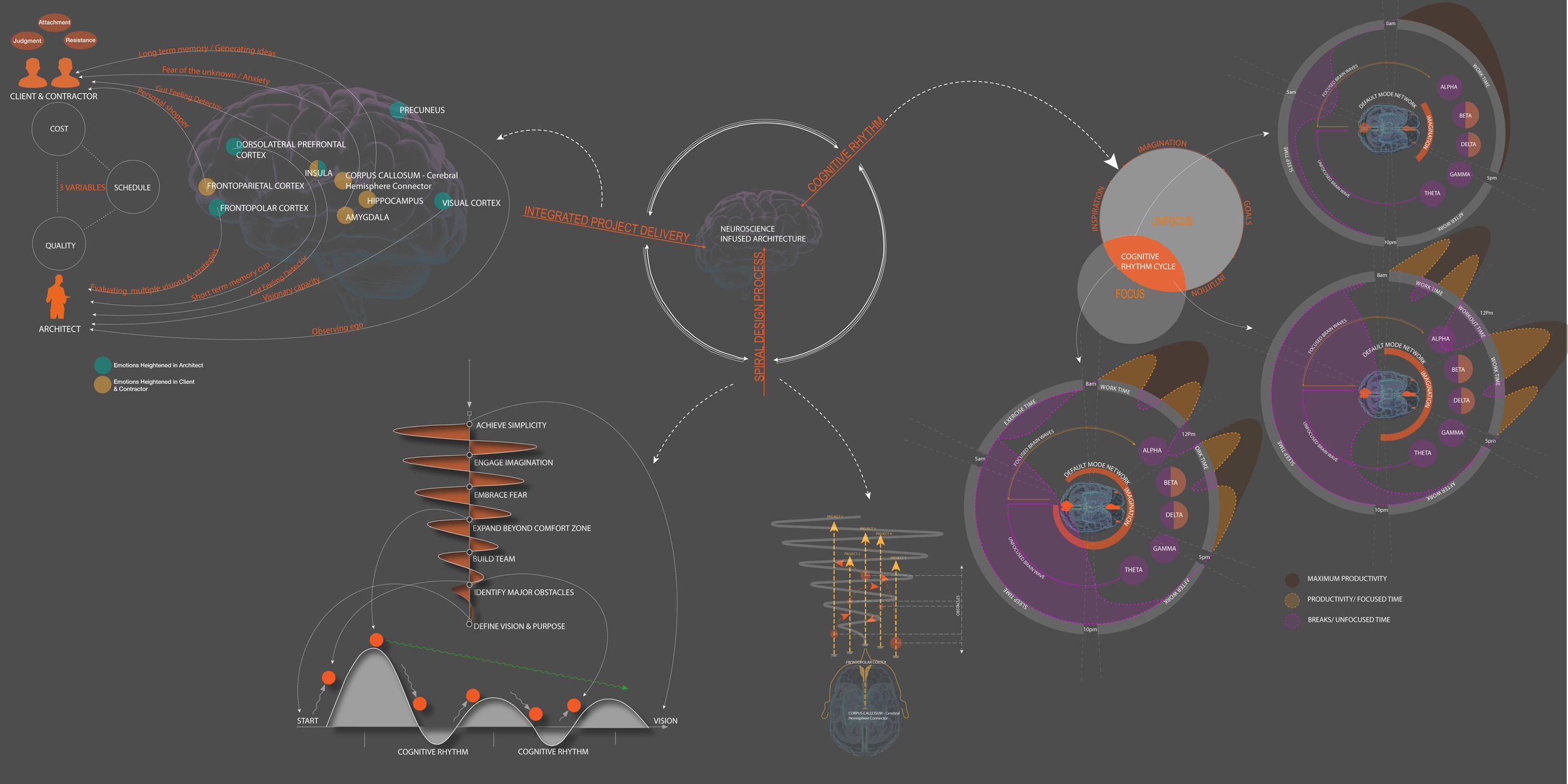

“Architecture and neuroscience are deeply interconnected, influencing the evolving role of the architect. By understanding how the brain functions, provides ability create a clear project vision, and employ the skills required to identify and overcome primary obstacles to enhance smooth-flowing design, client, and construction team relationships.”

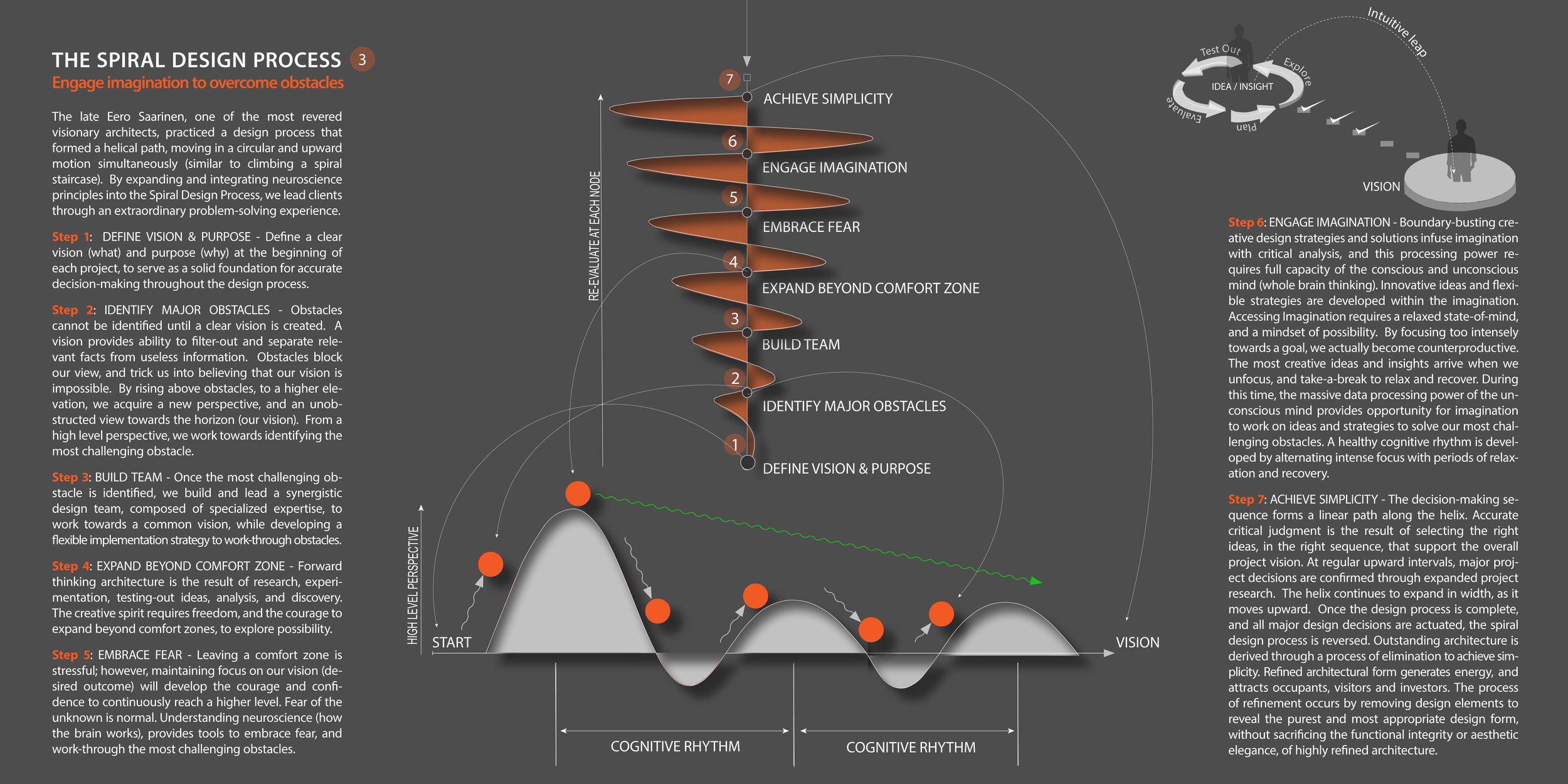

We coach clients to learn exceptional creative problem-solving strategies and skills, while working-through our Spiral Design Process…

By expanding and integrating neuroscience principles into the Spiral Design Process, we lead clients through an extraordinary, life-changing experience.

Forward-Thinking Architecture Requires Courage To Expand Beyond Comfort Zones

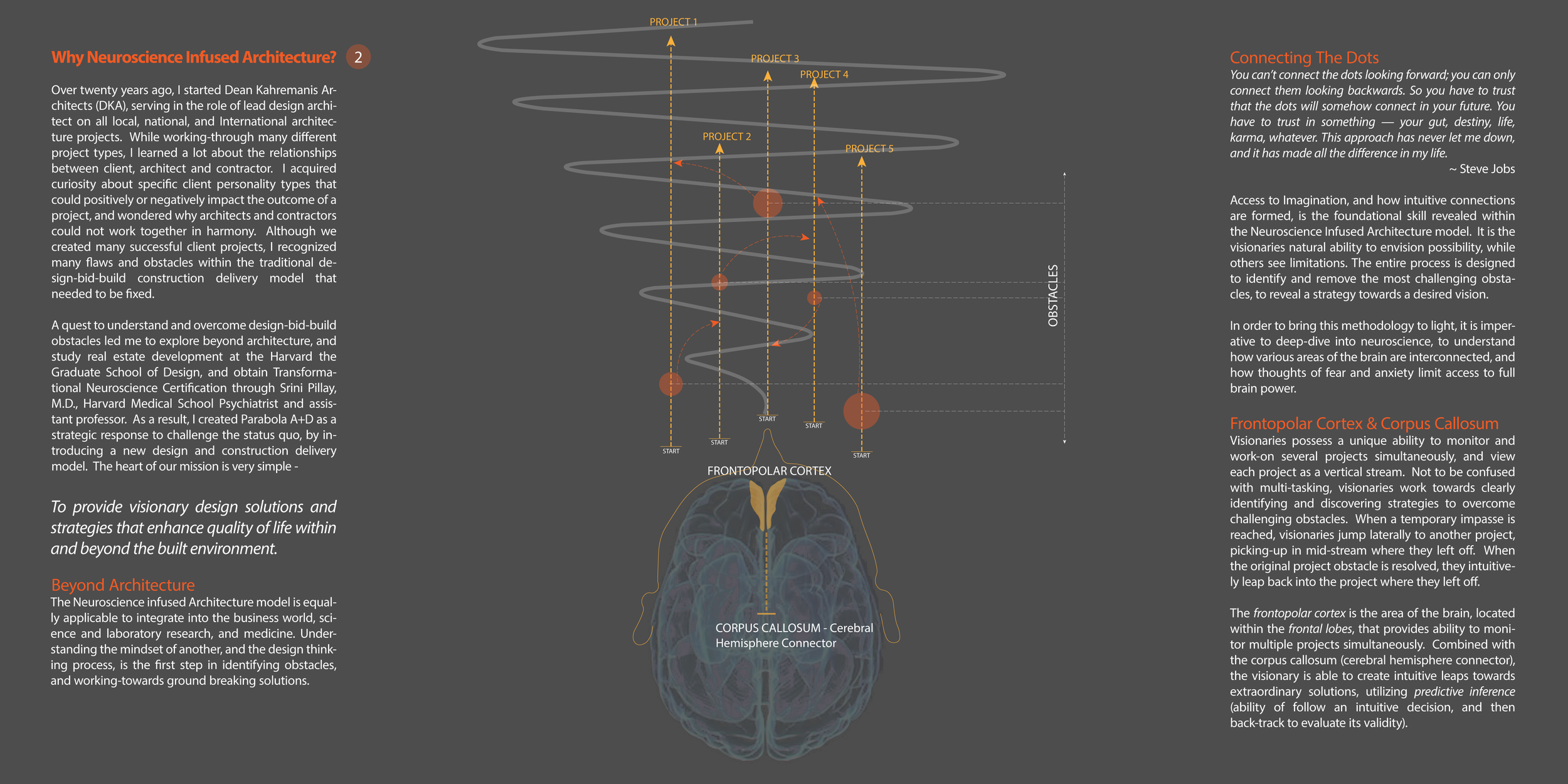

Creating outstanding architecture is the result of research, experimentation, analysis, and discovery. The creative spirit requires freedom and courage to depart from comfort zones to soar into the realm of possibility. Our design process infuses imagination with critical analysis, requiring full capacity of the conscious and unconscious mind (whole brain thinking). The creative design process is a combination of parallel and sequential experimentation, intuitive insights, and accurate critical judgement.

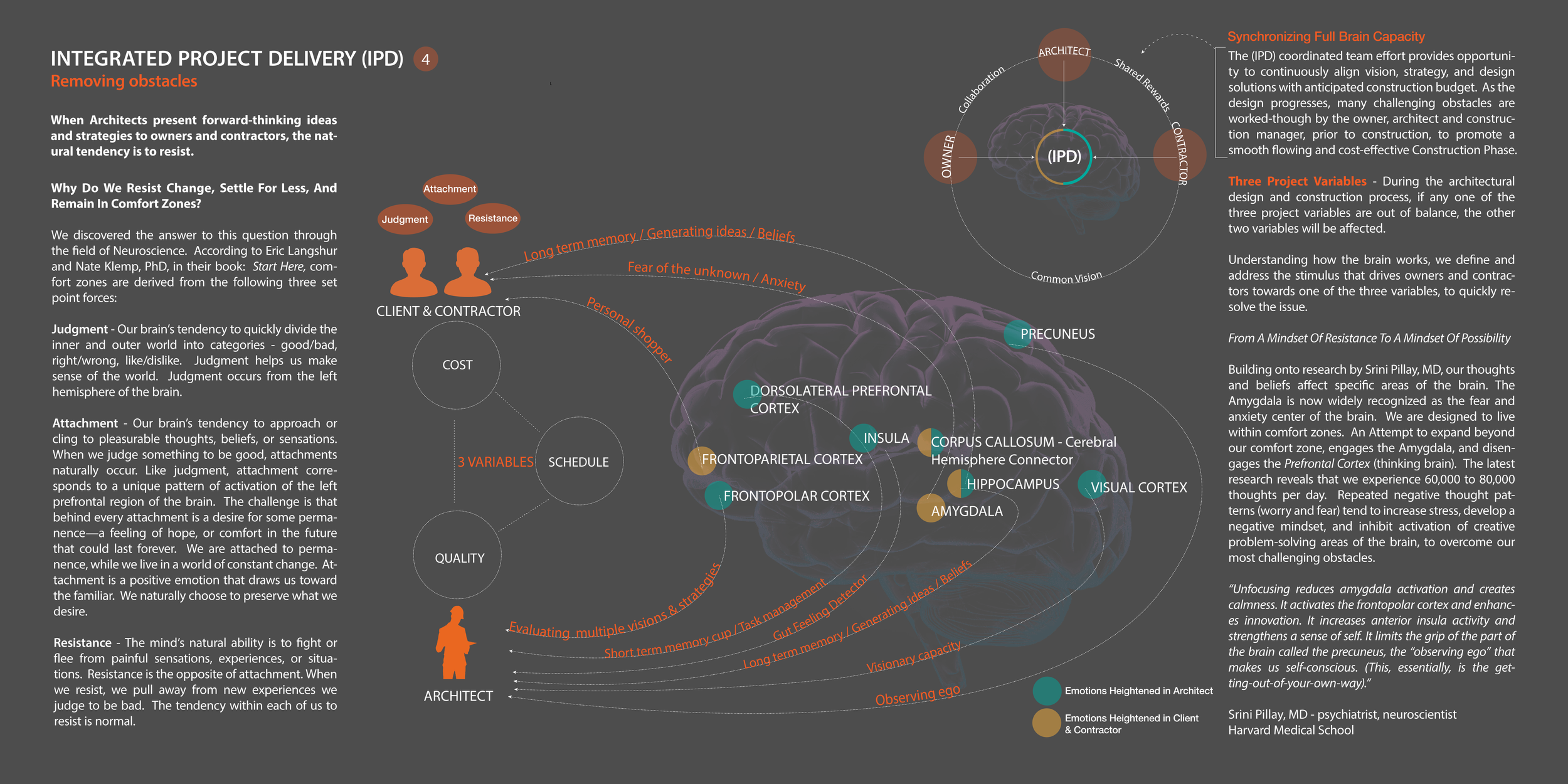

Neuroscience infused architecture fosters harmonious client, architecture & construction relationships

Architecture and neuroscience share a close and interdependent relationship that profoundly influences the evolving role of the architect. Gaining an understanding of how the brain functions not only empowers architects to refine each project vision but also provides the ability to navigate and surmount key obstacles.

The integration of neuroscience into architecture enables architects to comprehend how individuals perceive and respond to built environment. By considering aspects such as spatial configuration, light, color, materials, and acoustics through the lens of neuroscience, architects can design spaces that elicit specific emotional and physiological responses in occupants. Furthermore, delving into the realm of neuroscience equips architects with the cognitive tools to effectively communicate and collaborate with clients and construction teams. This deeper understanding of human cognition and behavior enables architects to empathetically engage with clients to decipher and translate their unspoken needs into tangible architectural solutions. Additionally, leveraging neuroscience principles can facilitate the creation of spaces that optimize cognitive and emotional well-being.

By harnessing insights from neuroscience, architects are better positioned to anticipate and address the multifaceted challenges that arise during the design, development, and construction process. Understanding the mindset of various stakeholders allows architects to proactively identify and mitigate potential points of friction, thereby fostering a smoother and more cohesive project execution.

A Mindset of Possibility

Ongoing research by Srini Pillay, MD, psychiatrist, neuroscientist, and leading brain researcher at Harvard Medical School, has identified how our thoughts and beliefs affect specific areas of the brain. The Amygdala is now widely recognized as the fear and anxiety center of the brain. As human beings, we are designed to live within comfort zones. Attempting to expand beyond our comfort zone, engages the Amygdala.

Amygdala - fear center of the brain

When the Amygdala is activated, the Prefrontal Cortex (thinking brain) is disengaged. The latest research reveals that we experience 60,000 to 80,000 thoughts per day. Repeated negative thought patterns (worry and fear) tend to increase stress, develop a negative mindset, and inhibit activation of creative problem-solving areas of the brain, to overcome our most challenging obstacles.

In Tinker Dabble Doodle Try, Dr. Pillay reveals how focusing too intensely towards a goal becomes counterproductive. Creating a healthy cognitive rhythm (focus and unfocus time), allows the brain to process information and recover. In fact, Dr. Pillay’s research indicates that a focused, conscious brain processes information at 60 bits per second at best, while the unconscious brain processes information at approximately 11 million bits per second. Dr. Pillay has coined the term of developing a “mindset of possibility.”

Frontal Lobe & Frontopolar Cortex - enhances innovation

“Unfocusing reduces amygdala activation and creates calmness. It activates the frontopolar cortex and enhances innovation. It increases anterior insula activity and strengthens a sense of self. It limits the grip of the part of the brain called the precuneus, the “observing ego” that makes us self-conscious. (This, essentially, is the getting-out-of-your-own-way).”

Why we resist change, settle for less, and remain in comfort zones

We discovered the answer to this question through the field of Neuroscience. According to Eric Langshur and Nate Klemp, PhD, in their book: Start Here, comfort zones are derived from the following three set point forces:

-

Our brain’s tendency to quickly divide the inner and outer world into categories—good/bad, right/wrong, like/dislike. Judgment helps us make sense of the world. Judgment occurs from the left hemisphere of the brain.

-

Our brain’s tendency to approach or cling to pleasurable thoughts, beliefs, or sensations. When we judge something to be good, attachments naturally occur. Like judgment, attachment corresponds to a unique pattern of activation of the left prefrontal region of the brain. The challenge is that behind every attachment is a desire for some permanence—a feeling of hope, or comfort in the future that could last forever. This is the root of the problem - we are attached to permanence, while we live in a world of constant change. Attachment is a positive emotion that draws us toward the familiar. We naturally choose to preserve what we desire.

-

The mind’s natural ability is to fight or flee from painful sensations, experiences, or situations. Resistance is the opposite of attachment. When we resist, we pull away: We fight or flee from new experiences we judge to be bad. The tendency within each of us to resist is normal. When we are presented with ideas that we are not accustomed to, we tend to resist, or allow negative thought patterns to spiral out of control. What happens in the brain when we resist? According to Klemp, the pattern of activation in the brain shifts from the left to the right frontal region of the brain to the Amygdala—the region associated with fear and avoidance.